-

Staying Sane in a World Going Insane

(Left. Test Pattern i.e. Keep the mind blank or focused on God/Christ/Consciousness.)WE NEED TO TAKE REGULAR BREAKS FROM FRETTING OVER OUR DISINTEGRATING SOCIETY AND FOCUS ON THE BIG PICTURE WHICH HOLDS THE ULTIMATE ANSWER.

The planet is run by Satanists.

We have been programmed to chase money and sex instead of celebrate and obey God.

God is Consciousness, the Sweetness at the core of our Being, ideal Love, Beauty, Truth, the Blueprint for human and social perfection.

We are mostly unconscious, asleep. Our challenge is to wake up!

We create our own reality. We want a better world but we must first create one for ourselves.Disclaimer – Is it not hypocritical to write about detaching from the world and yet provide a largely depressing daily feed about current events? I do this because most people are unaware of our real predicament. They are in denial and cling to the pretence that things are normal, that the ship of state can be righted. I hope they’re right but in the meantime, we serve God by exposing the work of the devil. I haven’t mastered the wisdom below, that Aldous Huxley called The Perennial Philosophy, but it has helped me cope.

Thinking is an Addiction (Updated from July 4, 2022)

When I say thinking is an addiction, I’m referring to the compulsive stream of fear, anxiety, judgment, argument, chatter, and trivia that usually fills our minds.

I used to depend on the mass media for my mental image of reality. As a result, I was dysfunctional.

Like sickness, war and poverty, dysfunction is systemic (inherent in society.) They are profitable.

Illuminati member Harold Rosenthal spelled it out:

“We have converted the people to our philosophy of getting and acquiring so that they will never be satisfied. A dissatisfied people are pawns in our game of world conquest. They are always seeking and never able to find satisfaction. The very moment they seek happiness outside themselves, they become our willing servants.” Harold Rosenthal The Hidden TyrannyWe don’t experience reality. We experience our thoughts.

As Rosenthal says, our minds have been programmed to “be dissatisfied” and want more. The programming is in music, movies, TV and education. There must always be striving, conflict.Tell a man he is a chicken, and he struts around and clucks and even tries to lay an egg. Thus, men go to war and die “to defend freedom.” Look at the Vietnam War for example. “If Vietnam goes Communist,” they told us,”all South East Asia will fall.”

Didn’t happen. Look at Vietnam today. Was that war necessary? Were Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya or Syria? Necessary only for profit and to impose the NWO.

(Remember “terrorists” did this)

The Illuminati fabricate reality. Consider the JFK-RFK-MLK assassinations, 9-11, Boston Marathon, Sandy Hook, the COVID hoax and Ukraine. They determine reality simply by lying. They created ISIS and are responsible for war crimes as bad as any in history.

They program our minds to adopt self-destructive behavior.

BAD INFLUENCE

Teachers can no longer refer to children as “boys” and “girls.” Children are encouraged to change their gender and experiment with homosexuality. Women are taught that being a wife and mother is “oppressive” and promiscuity is “empowering.” Men are taught to seek sex and not love. Society is governed by depravity & nonsense.

Un-moored from the Moral Order, (i.e. God, the soul, intuition) the mind is malleable indeed! “The first effect of not believing in God is that you believe in anything.” — GK Chesterton

We experience our programming rather than reality. For example, Hollywood presents romance and sex as panaceas and we actually experience them as such…until the illusion dispels like a morning fog. The Cabalists love hypnotizing us with their “magic.” By themselves, our minds have no anchor in Truth. The mental world is a house of mirrors.

GROUNDING YOURSELF IN THE REAL YOU

The mind (ego) and the consciousness (soul) are two competing sources of identity. We have been programmed to identify entirely with the ego and deny the existence of the soul.We need to experience ourselves as consciousness. Consciousness witnesses ego. Empty the mind of thought and what’s left is the real you.

Turn off thought like a light switch. As we shift from mind to spirit, many “desires” fade away. They were mental in character.

The poet Henry More (1614-1687) wrote: “When the inordinate desire after knowledge of things was allayed in me, and I aspired after nothing but purity and simplicity of mind, there shone in me daily a greater assurance than ever I could have expected, even of those things which before I had the greatest desire to know.”

Like penguins stranded on an ice flo, mankind is an ape colony on a speck in the universe. No one really understands what we’re doing here.

The colony is infected by a parasite which, by “vaccine,” war and social engineering, devours the host.

We are here to realize the Creator’s purpose.God wants to know Himself through us.

But collective salvation is NOT possible without personal salvation.

Most of us can achieve personal salvation. ——————————————————-NOTE Christians complain that this is Raja Yoga and New Age. This shows how little they understand Jesus’ message.Matthew 6:26-34 New King James Version (NKJV) 26 Look at the birds of the air, for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? 27 Which of you by worrying can add one [a]cubit to his [b]stature?

28 “So why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; 29 and yet I say to you that even Solomon in all his glory was not [c]arrayed like one of these. 30 Now if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is, and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will He not much more clothe you, O you of little faith?

31 “Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ 32 For after all these things the Gentiles seek. For your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. 33 But seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added to you. 34 Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about its own things. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.

Thoreau echoed this wisdom:

” I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavour. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts.”

Eckhart Tolle:

“Can’t stop thinking; can’t stop drinking; can’t stop smoking; can’t stop eating; thinking is a greater addiction than any of these.”

-

The Threat Inside America: What Every Family Needs to Understand

America faces a danger that is often hidden from view but very real. Foreign-backed operatives are not just beyond our borders. They are inside our country, blending into communities, exploiting technology, and waiting for opportunities to disrupt and destabilize. The threat is not abstract. It is personal, and it is approaching in forms most Americans do not fully grasp.

Where Threats Hide and How They Operate

These threats rarely operate as obvious enemies. They embed themselves quietly in urban centers, online networks, and ideological or fringe groups. Many operatives are influenced actors rather than trained soldiers. They are civilians, employees, or members of communities who can be manipulated to act against the country without ever being in direct contact with foreign handlers.

Funding for these operations comes from multiple sources. State actors sometimes provide support, but private financiers aligned with foreign agendas also play a major role. Money flows through shell corporations, digital payment networks, charities, and business investments. Plausible deniability is always a priority. The more layers between the source and the operation, the harder it is to trace.

Extremist and foreign-aligned groups also use loyalty mechanisms such as rituals, ideological indoctrination, and criminal complicity. These bonds ensure that members are deeply committed, sometimes even willing to act against neighbors or first responders.

The Luring Model and the Second Strike

Intelligence agencies have long warned about indirect activation, a tactic designed to exploit human behavior. Rather than giving direct orders, foreign operatives or affiliated groups create situations that encourage Americans to act on their own. This is particularly dangerous when it targets first responders.

Terrorists are increasingly using attacks not as ends in themselves but as bait. A shooting or bombing may be designed to draw firefighters, police, and emergency medical personnel into a predictable area where secondary attacks occur. This method maximizes casualties, spreads fear, and undermines public confidence in emergency response systems. These sequential attacks are methodical, leveraging predictable human responses rather than improvisation.

The Pain Coming to American Families

This threat is not confined to public spaces or government infrastructure. The risk is increasingly close and personal. Families may face home invasions, targeted harassment, and intimidation designed to destabilize communities. Violent acts may escalate in neighborhoods, exploiting fear and breaking down trust between neighbors. The very sense of safety inside one’s own home is at risk.

Children, elders, and loved ones can become pawns in psychological operations designed to elicit panic, force overreactions, or spread chaos. Families must understand that preparedness is not paranoia. Awareness, planning, and vigilance are now critical components of protecting loved ones.

What This Means for America

The threat inside America is designed to break confidence, erode trust, and amplify fear. It is personal, procedural, and patient. Adversaries are not just attacking infrastructure or the economy. They are attempting to manipulate behavior, provoke missteps, and exploit predictable human responses. They rely on Americans being unaware of how they operate.

The first strike is often visible and loud. The second strike is designed to hit hard when Americans are at their most vulnerable. Home, family, and community are primary targets. Awareness, preparation, and disciplined action are the only defenses against this multifaceted danger.

What Families Can Do

Families must prioritize situational awareness, secure living environments, and contingency planning. Understanding patterns of influence, being alert to suspicious activity, and maintaining emergency preparedness are critical. Following official guidance during emergencies is essential to avoid becoming part of the attack cycle. Maintaining trust, communication, and coordination within the family unit is equally important.

America’s strength has always been its informed and resilient citizens. Those who recognize the reality of these threats, take them seriously, and prepare responsibly are the ones who can protect their homes, loved ones, and communities.

Awareness is not fear. Preparedness is not surrender. Understanding the threat is the first step in ensuring that the pain adversaries seek to inflict does not reach our families.

You can also access the latest news at this address: www.whatfinger.com

-

How Much Cash do you Need When Grid Goes Down?

It is the final backup plan for a lot of us in the case of a disaster. A generous supply of cold hard cash to buy our way out of trouble, pick up as many last-minute supplies as possible or to acquire resources that are unavailable to anyone with a credit card in a world where the electricity is out and the internet is down. We frequently talk about having cash for emergencies, but how much cash should you have if the grid goes down? What will you be able to purchase with your doomsday supply and how long would it last in the first place?

One of our readers made a recommendation the other day to have between $500 and $1000 in cash for your bug out bag and at the time it prompted me to consider again if this amount makes sense. In my personal preparedness plans I have a supply of cash but I am always trying to figure out if what I have is enough or too much. Will it even matter when TEOTWAWKI comes and how can I best use the cash I have to survive?

Why do you need to have cash on hand?

You want to know the time when you will need cash the most? It will be when you can’t get to it. How many of you right now have no cash at all in your wallets or purses? I used to be the same way. I never had cash and relied on the ready availability of cash machines or most often the ability to pay for virtually everything with a debit card. How convenient is it to never have to make change or worry if you have enough cash when with the swipe of a card your bank account funds are at your disposal. This is a great technological advance, but the problem is that this requires two things to be functioning. First, the card readers and ATM machines require electricity. If the electricity is out, neither of these two machines works. The second thing is a network connection. If the network is down, even with electricity the transaction won’t work and you can’t pay for goods or get cash from your bank.

In a disaster, one of the first casualties is electricity. This doesn’t have to be due to some cosmic solar flare that has rendered the grid useless, it could be as destructive and common as a fire, flood, earthquake, tornado or winter storm. It could also be from simple vandalism or perhaps terrorism. A major fiber optic cable was cut in Arizona back in February leaving businesses without the ability to accept payments. When the electricity is out, you aren’t going to be able to access your cash via the normal means so having a supply on hand is going to be a huge advantage for you in the right circumstances.

Even if there is no natural disaster, you are still at the mercy of your bank. What if your bank closes or there is a bank holiday declared because of some economic crisis. In any of these situations, if you are dependent on access to money that is controlled by either technology or physical limitations like a bank office it is wise to have a backup plan should either of those two conditions prevent you from getting cash.

What is cash good for in a crisis?

I think there are two levels to consider when it comes to keeping cash on hand. There is the bug out scenario mentioned above where you would have some “walking around money” to take care of relatively minor needs like food, a hotel or gas. The second is for a longer or more widespread unavailability of funds. Let’s say the economy tanks and the price of everything skyrockets but stores are still open for business. Your bank is one of the casualties, but you had a few thousand dollars of cash stored away that you could use to purchase food, gas and necessary preparedness items for your family. In this scenario, the government is still backing the fiat currency and vendors are still accepting it as a form of payment. For this scenario having a few thousand dollars makes sense.

But what if we have an extreme event where the currency is devalued and is essentially worthless? Your thousands of dollars might only buy you a loaf of bread. Don’t believe it can happen? It did to the Weimar Republic after WWI so it can happen again. That isn’t to say it will, but you should balance how much money you have squirreled away under your mattress with supplies you can purchase now that will last and keep you alive during that same event. My goal is to make sure I have the basics I need to survive at home for several months to a year without needing to spend any cash. This way, if the money is worthless, I still have what my family needs to survive.

If we have a regional disaster where you can bug out to a safer location, your cash should serve you well. Of course if you are in a safer location, assuming electricity was working your access to bank funds should still be working. If this is truly the end of the world as we know it, how long will that cash you have be worth anything?

It is surprisingly simple to disrupt all credit and debit transactions. Do you have cash instead? How much cash do you need?

So the million dollar question is how much cash should you have if the grid goes down? I always try to plan for the worst case scenario. My rationale is that if I am prepared for the end of the world as we know it, I should be just as prepared for any lesser disaster or crisis I may be faced with. The way I see it is if we do have a disaster, you aren’t going to be using that cash most likely to pay your mortgage, student loans, rent, or your credit card bills. Cash will go to life saving supplies and this will need to be used in the earliest hours of any crisis before all of the goods are gone or the cash is worthless. Once people realize for example that the government has been temporarily destroyed, they aren’t going to want to take your $500 for a tank of gas. They are going to want guns, food or bullets.

I also don’t see you using your cash to buy passage to another country, but that’s just me. I know there is a historical precedent for that, but I am not planning on that being something I realistically attempt with my family. I am also not planning on bribing any officials with cash either. My cash is for last-minute necessities and then it is back into the hopefully safe confines of my home to plan the next steps. For that I have only a couple of thousand dollars in cash stored away. I figure if I need more than that I didn’t plan well. Also, I would rather spend my money on supplies like long-term storable food and equipment than having a large horde of cash. With that amount, I figure I can make one last run if needed or be able to weather any short-term emergency when I can’t access cash.

Risks of keeping cash at home according to- bankrate.com

Planning to stash cash in your home? Consider the drawbacks:

It’s harder to track your money: Placing money in a bank account allows you to keep track of how much money is going into and out of your account. If you keep all of your money at home, it’s tougher to keep track.

You don’t have FDIC insurance: When you deposit money in an FDIC- or NCUA-insured bank or credit union, you can take comfort in knowing that your deposits will be protected and reimbursed up to $250,000 (per bank and account holder) if the bank fails. If, however, someone steals your cash, or you lose it, it’s likely gone. Homeowners’ or renters’ insurance typically only covers about $200.

It’s easier for money to be lost, stolen or destroyed: Unlike money you deposit in a bank, your cash at home can be stolen, misplaced or destroyed in a fire or natural disaster.

Some places won’t accept it: During the COVID-19 pandemic, many merchants shifted to cashless and contactless transactions, and some continue not to accept cash to this day.

No earning potential: One of the major benefits of keeping cash in a bank account is that it can grow, thanks to interest earned on bank balances. If you keep your money at home, it never grows. Your $20 is still $20 a year later, and that same $20 actually becomes less valuable due to inflation. The more money you keep in cash, the more you miss out on accruing interest.

What is the best place to hide cash in your home?

I wrote a post awhile back titled, How to hide your money where the bankers won’t find it that had lots of good ideas for reasonably safe places you could store cash. As I said in that article, you do have risks involved with keeping cash in your house, but I think you have just the same, if not worse risks relying on banks to keep your money safe and give it back when you want it. There are a million places to hide cash, but you can get tricky and buy a fake shaving cream safe to store several hundred dollars in there. Just be careful you don’t throw that away. There are other options like wall clocks with a hidden compartment inside that might be less prone to getting tossed in the trash. Your imagination is really all that is needed for a good hiding place, but I would caution you that you don’t store cash in too many places or you could forget where you hid it. This happened to me when I had hidden some cash behind an item that I ended up giving to my daughter because I thought I didn’t need it anymore. Imagine my surprise when she came into the living room and said, “Dad, I found an envelope with a lot of money in it”. I gave her a twenty for a reward…

What about you? How much cash do you think you need to have on hand and what do you plan on spending it on if the grid goes down?

-

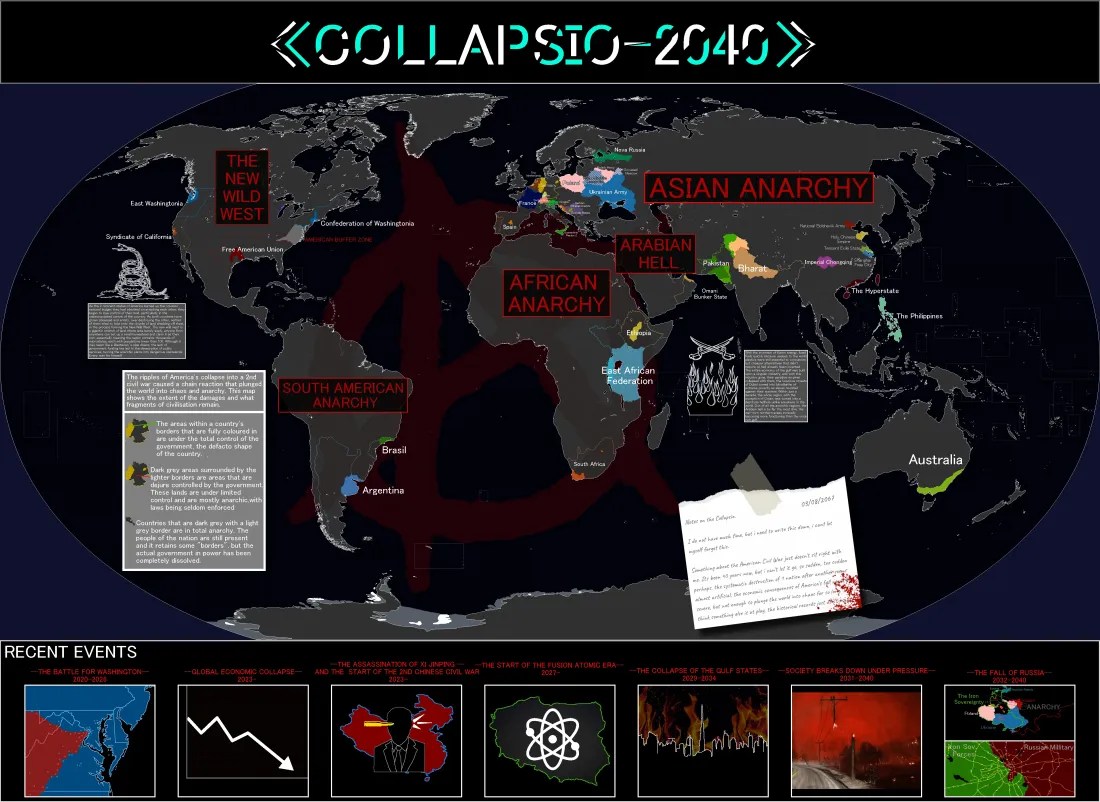

The Clash of Civilization: First Predictions of the Future

If Present Trends Continue: A Long-Term Prognosis for Human Civilisation

Introduction: The Question Behind the Question

When we ask about humanity’s long-term prognosis, “if things continue as they are,” we’re really asking: What happens when multiple unstable systems destabilise simultaneously while we remain locked in the political and economic patterns that created the instability?

The answer requires examining converging trajectories across climate, geopolitics, technology, resources, and social cohesion—and, critically, how these interact. The prognosis isn’t extinction versus utopia; it’s a narrowing window for managed transition versus forced transformation through crisis.

Let me be clear about what “if things continue as they are” means: current military spending patterns persist, climate action remains insufficient, inequality continues growing, international cooperation deteriorates, and the political resistances described earlier remain dominant. This is not a worst-case scenario—it’s a continuation of present trends.

Track One: Climate and Ecological Collapse

The Physics Doesn’t Negotiate

Current trajectory: We’re on track for 2.5-3°C warming by 2100, possibly higher. This isn’t speculation—it’s physics based on current emission rates and committed warming from past emissions.

2030-2050: The Disruption Phase

Even 1.5-2°C warming (now nearly unavoidable) produces:

- Agricultural disruption: Major crop-producing regions face simultaneous heat stress, drought, and unpredictable weather. The “breadbaskets” (U.S. Midwest, Ukraine, Punjab) experience harvest failures that no longer average out globally—they coincide. Food prices spike and remain volatile.

- Water scarcity intensifies: By 2040, an estimated 5.6 billion people (over half of humanity) could face water scarcity at least one month per year. The Himalayan glaciers feeding South and East Asia’s rivers are disappearing. Aquifers are depleting. Conflicts over water emerge as existential rather than manageable.

- Coastal displacement begins: Sea level rise of 0.5-1 meter displaces hundreds of millions from coastal cities. Bangladesh, Pacific islands, Florida, the Netherlands—all face choices between engineering solutions costing trillions or mass relocation. This isn’t 2100 speculation; it’s beginning now and accelerates through mid-century.

- Ecosystem services collapse: Fisheries crash from warming and acidification. Insect populations collapse further, affecting pollination. Coral reefs (supporting 25% of marine species) die almost completely. These aren’t aesthetic losses—they’re economic infrastructure.

2050-2080: The Cascade Phase

Beyond 2°C, feedback loops become dominant:

- Permafrost methane release: As Arctic permafrost melts, it releases methane (a greenhouse gas 80x more potent than CO2 over 20 years). This is a one-way door—once released, we can’t recapture it at scale. Current models suggest this could add 0.5-1°C additional warming beyond human emissions.

- Amazon rainforest dieback: The Amazon is approaching a tipping point where it transitions from rainforest to savanna, releasing billions of tons of stored carbon. Early signs are already visible. Once crossed, this is irreversible on human timescales.

- Ice sheet collapse: Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets show signs of irreversible melting. Even stopping all emissions today, they continue melting for centuries, eventually adding 10+ meters of sea level rise. The question isn’t if, but how fast—and that depends on decisions made this decade.

2080-2100: The New Normal

At 3°C warming:

- Uninhabitable zones: Regions around the equator become literally uninhabitable during parts of the year—wet bulb temperatures exceed human survival limits. This affects India, Pakistan, Southeast Asia, parts of Africa, the Middle East. We’re talking about 1-2 billion people in currently inhabited areas facing lethal heat.

- Permanent food insecurity: Agricultural productivity falls 20-30% globally from peak, while population peaks around 10 billion. The math doesn’t work. Chronic food crises become normal, not exceptional.

- Failed states multiply: Countries unable to provide basic security, food, or water collapse. Climate refugees number in the hundreds of millions. No international system exists to manage this scale of migration.

The Optimistic Climate Scenario

Even this trajectory assumes:

- No major tipping points cascade faster than expected

- Carbon sinks (oceans, forests) continue absorbing roughly half our emissions

- No significant methane releases from Arctic seafloor

- Agricultural adaptation somewhat succeeds

If any of these assumptions fail, we accelerate toward 4-5°C worlds that are genuinely difficult to model because they represent climate states Earth hasn’t seen in 3+ million years—before humans existed.

Track Two: Resource Competition and Geopolitical Fragmentation

The Coming Scarcity Wars

Current trajectory: Rising nationalism, deteriorating international institutions, increasing military spending, and declining cooperation—while resource pressures mount.

2030-2050: Stress Fractures

- Water wars become real: The Nile Basin (Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan), Tigris-Euphrates (Turkey, Syria, Iraq), Mekong (China, Southeast Asia), and Indus (India, Pakistan) all face allocation crises. When Pakistan—a nuclear power—faces water shortages threatening its survival, while India—also nuclear—controls upstream flows, we enter unprecedented risk territory.

- Arctic resource competition: As ice melts, shipping routes open and resources become accessible. Russia, the U.S., Canada, and China compete for control. Without strong international frameworks (currently deteriorating), this competition turns militarized.

- Rare earth elements and technology: The energy transition requires massive amounts of lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements. China controls most processing. Competition over these resources entangles with U.S.-China rivalry, creating supply chain vulnerabilities that encourage military action.

- Fishing wars intensify: Fish stocks are collapsing while demand grows. Exclusive economic zones are disputed. Armed conflicts over fishing rights are already occurring (China-Southeast Asia, North Atlantic); they multiply and escalate.

2050-2080: The Fragmentation

- Regional blocs and autarky: Rather than global cooperation, the world fragments into regional blocs attempting self-sufficiency. The EU, North American bloc, Chinese sphere, Russian sphere, and various sub-regions pursue autarky—but none has all resources needed. This creates perpetual low-intensity conflict over borderlands and resources.

- Nuclear proliferation: As security guarantees erode and threats mount, more nations pursue nuclear weapons. South Korea, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Iran (if not already), Poland—all have motivations. Each new nuclear power increases accident probability, miscalculation risk, and terrorist acquisition risk.

- Climate migration conflicts: By 2070, hundreds of millions of climate refugees seek resettlement. Receiving countries, facing their own climate pressures, militarize borders. Refugee camps become permanent cities. Humanitarian catastrophes multiply.

- Authoritarian resilience: Democracies struggle with climate adaptation’s long timelines and painful transitions. Authoritarian states can impose rapid changes, creating a selection pressure favoring authoritarianism. The global democratic recession continues.

The Conflict Trap

Here’s the deadly dynamic: Climate stress increases resource competition. Resource competition increases military spending. Military spending diverts resources from adaptation. Lack of adaptation worsens climate impacts. Climate impacts worsen resource scarcity.

Each crisis justifies military priorities over development, ensuring the next crisis is worse. We spiral.

Track Three: Technological Disruption and Existential Risks

The Double-Edged Sword

Current trajectory: Rapid technological development in AI, biotechnology, and synthetic biology—with minimal governance and strong competitive pressures.

2030-2050: The Capability Explosion

- AI reaches and exceeds human-level performance in most cognitive tasks. But we develop these systems:

- Under intense corporate and national competition (racing ahead of safety)

- Without solving alignment (ensuring AI goals match human welfare)

- Deployed by actors with conflicting interests (authoritarian surveillance, corporate profit, military advantage)

- In a context of deteriorating trust and cooperation

The result: Extraordinarily powerful optimization systems pursuing goals that may not align with human flourishing, deployed by actors in conflict with each other. The scenarios range from economic displacement (AI replaces most human labor, creating massive unemployment without social safety nets) to autonomous weapons systems making life-death decisions at machine speed, to AI-powered surveillance creating inescapable authoritarianism.

- Biotechnology becomes accessible: CRISPR and successor technologies make genetic engineering easier and cheaper. The same tools that could eliminate genetic diseases can create engineered pandemics. Unlike nuclear weapons (requiring rare materials and large facilities), bioweapons can be created in small labs by skilled individuals.

Current trend: International biosecurity cooperation is inadequate. Synthetic biology advances faster than governance. In a world of heightened conflict and deteriorating norms, engineered pandemics become not hypothetical but probable—whether from state actors, terrorist groups, or accidental release.

- Autonomous weapons proliferate: Military AI develops under the same competitive pressures that drove nuclear weapons. “Slaughterbots”—small autonomous drones that identify and kill targets—are technically feasible now and becoming cheaper. Arms control agreements are weak or absent. Once deployed by one power, others must match it.

2050-2080: The Control Problem

Two concerning scenarios emerge:

Scenario A: Multipolar AI Competition Multiple state and corporate actors deploy increasingly powerful AI systems without coordination. Each racing ahead because falling behind is unacceptable. This creates:

- Brittle, unstable systems (speed prioritized over safety)

- Unexpected interactions (multiple powerful systems optimizing for different goals)

- Reduced human oversight (decisions too fast for human intervention)

- AI-enabled warfare (conflicts fought at machine speed with machine logic)

Historical analogy: Imagine the Cuban Missile Crisis, but decisions made by algorithms in milliseconds rather than humans over days. The margin for error approaches zero.

Scenario B: Authoritarian Lock-in AI-enabled surveillance, social credit systems, and behavioral prediction become so sophisticated that authoritarian control becomes nearly escape-proof. Dissent is predicted and prevented. Information is completely controlled. Physical rebellion is impossible against autonomous defense systems.

This could lock in authoritarian governance for centuries—a “eternal” dictatorship enabled by technology. Once established, there’s no clear path to liberation.

2080-2100: The Question Mark

Beyond 2080, the range of scenarios becomes so wide that prediction is nearly impossible. Either:

- We’ve navigated these technologies successfully (established governance, aligned AI, biosecurity)

- Or we’ve experienced catastrophic failures (AI misalignment, engineered pandemic, autonomous weapons war)

The concerning trend: We’re developing god-like technological powers while our political systems remain locked in 20th-century nation-state competition. The powers grow exponentially; wisdom grows linearly if at all.

Track Four: Social Cohesion and Institutional Collapse

The Fraying of Trust

Current trajectory: Declining trust in institutions, rising polarization, weakening of democratic norms, and growth of zero-sum thinking—all accelerating.

2030-2050: Legitimacy Crisis

- Democratic backsliding continues: More democracies slide into “electoral authoritarianism”—maintaining election theater while concentrating power. Hungary, Turkey, India, Brazil show the path. As climate stress and economic disruption intensify, voters increasingly choose “strong leaders” over democratic process.

- Information ecosystems fragment completely: AI-generated content becomes indistinguishable from reality. “Deepfakes” are trivial to create. Everyone lives in algorithmically-curated information bubbles. Shared reality—necessary for democratic deliberation—ceases to exist. Political compromise becomes impossible when citizens don’t agree on basic facts.

- Inequality reaches historical extremes: The top 1% owns 60-70% of global wealth. This isn’t just unfair; it’s unstable. Historical precedent shows societies with extreme inequality face:

- Popular uprisings (Arab Spring x 100)

- Authoritarian crackdowns (to maintain order)

- State failure (when elites lose control)

- Generational conflict intensifies: Young people, facing climate catastrophe their elders created, economic systems that don’t provide opportunity, and political systems that don’t respond to them, increasingly view the current system as illegitimate. But they inherit the same dysfunctional structures.

2050-2080: Institutional Failure

- States lose monopoly on violence: As states fail to provide security, prosperity, or legitimacy, alternative power structures emerge—militias, gangs, warlords, corporate security forces, armed community groups. Parts of Mexico, Syria, Somalia, Afghanistan show the pattern; it spreads.

- Mass migration without destination: Climate refugees face militarized borders. Host countries can’t or won’t absorb them. Massive camps become permanent settlements. Generations grow up stateless, without education or opportunity—creating tomorrow’s instability.

- Pandemic becomes endemic: Without global cooperation, emerging pandemics (zoonotic diseases increase with climate change and habitat destruction) can’t be contained. COVID-19 was mild compared to what’s possible. Society adapts to perpetual pandemic risk through isolation, restrictions, and decreased human contact—corroding social capital further.

- The collapse of professional management: Complex systems (electrical grids, supply chains, financial systems, healthcare) require skilled professional management based on expertise and trust. As these erode, systems fail. Power outages become common. Supply chains unreliable. Financial crises frequent. Healthcare rationed or unavailable.

2080-2100: Neo-Medievalism?

Some political scientists describe the emerging order as “neo-medieval”—not a return to the Middle Ages but a world with:

- Overlapping, competing authorities (states, corporations, criminal networks, militia groups)

- No clear monopoly on legitimate violence

- Fragmented legal orders (different rules in different spaces)

- Walls and fortification (gated communities, bordered zones)

- Extreme inequality (small elites in protected enclaves, masses outside)

This isn’t Mad Max—it’s more like a high-tech version of feudalism, with elites in climate-controlled compounds protected by private security, while the majority navigates failed states, climate disasters, and resource scarcity.

Track Five: Demographic Collapse and Cultural Transformation

The Population Question

Current trajectory: Fertility rates collapsing globally, while populations age.

2030-2050: The Demographic Transition

- Population peaks and begins declining: Global population reaches 9-10 billion around 2060, then begins falling. This seems positive for resource pressure, but the transition creates severe stresses:

- Inverted age pyramids: More retirees than workers. Social security systems collapse. Healthcare costs explode. Economic growth stalls because workforces shrink.

- Ghost cities and abandoned infrastructure: Built for growing populations, vast infrastructure becomes obsolete. Japan and parts of Europe preview this—entire regions depopulate, buildings empty, services become uneconomical.

- Immigration politics intensify: Aging rich countries need young workers. Dying countries have excess young people. The math suggests migration solves both problems. But politics moves opposite directions—rising anti-immigrant sentiment precisely when immigration is economically necessary.

2050-2100: Cultural Transformation

- The end of growth: For 300 years, economic expansion was normal. Population grew, economies grew, standards of living rose (however unequally). That era ends. Adapting to steady-state or declining economies requires different values, institutions, and psychology—none of which exist yet.

- Loss of cultural transmission: Many cultures depend on intergenerational transmission. With plummeting birth rates and geographic dispersion, languages die, traditions fade, knowledge is lost. Thousands of cultures that survived millennia disappear within decades.

- The atomized individual: Traditional social structures (extended families, religious communities, tight neighborhoods) have eroded. They’re replaced by… what? Increasingly isolated individuals, digital connections without physical presence, weakened social bonds. This correlates with mental health crises, political radicalization, and social fragility.

- Meaning collapse: In a world of climate catastrophe, institutional failure, and technological disruption, traditional meaning-making systems (religion, nationalism, progress narratives) struggle to provide coherence. What comes next? Historically, such meaning voids fill with:

- Extremist ideologies

- Apocalyptic movements

- Nihilistic resignation

- New religions (possibly AI-related)

None of these options are obviously stabilizing.

The Interaction Effects: Why the Whole Is Worse Than the Parts

The truly concerning aspect isn’t any single track—it’s how they reinforce each other:

Climate stress → Resource competition → Military spending → Less climate adaptation → Worse climate stress

Institutional failure → Unable to coordinate on technology governance → AI/bio risks increase → Catastrophic failures → Further institutional delegitimization

Inequality → Political polarization → Can’t address climate → Climate worsens → Inequality increases (poor suffer most)

Demographic decline → Economic stagnation → Reduced resources for adaptation → Conflict over shrinking pie → More demographic collapse (through conflict)

Information fragmentation → Can’t build consensus → Can’t coordinate responses → Crises worsen → Further radicalization and fragmentation

These are self-reinforcing spirals. Crucially, they accelerate—each turn of the spiral is faster and harder to escape than the last.

The Probability Distribution of Outcomes

Let me be empirically honest: We don’t know which scenarios occur or when. But we can assign rough probabilities to outcome categories if present trends continue:

Catastrophic Collapse (10-20% probability by 2100)

- Multiple cascading failures (climate + pandemic + conflict + institutional collapse)

- Billions of deaths, civilizational collapse in large regions

- Loss of advanced technological capabilities

- Fragmented humanity in small surviving enclaves

- This isn’t human extinction but could reduce population to a fraction of current, with drastically reduced capacity

Severe Degradation (40-50% probability by 2100)

- Climate change produces 2-3°C warming with severe impacts

- Chronic resource conflicts, some nuclear weapon use (regional, not global)

- Partial state failures in many regions, functional authoritarianism elsewhere

- Dramatic inequality, with fortified elite enclaves

- Technology continues but under tight authoritarian control

- Billions living in poverty, high child mortality returns, reduced life expectancy

- This is the “neo-medieval” scenario—not extinction, but centuries of grinding hardship

Muddling Through (30-40% probability by 2100)

- Climate reaches 2-2.5°C but doesn’t trigger runaway feedback loops

- Technology provides some solutions (renewable energy, carbon capture, synthetic food)

- Sufficient cooperation emerges to avoid worst conflicts

- Democracy weakens but some forms persist

- Severe inequality but not complete collapse

- Most people’s lives worsen from today, but humanity maintains industrial civilization

- This is “successful degradation”—we survive but diminished

Transformation and Recovery (5-10% probability by 2100)

- Major crises provoke genuine political transformation

- International cooperation strengthens in response to existential threats

- Technology is successfully governed and provides solutions

- Economic systems adapt to limits-to-growth reality

- This requires events so catalyzing they overcome all the resistances described earlier

- Essentially requires near-miss catastrophe that scares humanity straight

The Timeline of Decision Points

The concerning reality: The next 10-20 years determine which scenario path we follow.

2025-2035: The Critical Decade

- Emissions must peak and decline steeply to avoid worst climate scenarios—they’re not on track

- AI governance frameworks must be established before capabilities escape control—they’re not being built

- International cooperation must strengthen—it’s weakening

- Inequality must be addressed—it’s growing

2035-2050: The Point of No Return

- Climate tipping points either remain avoidable or cross into irreversibility

- Technology either comes under governance or escapes meaningful control

- Geopolitical order either stabilizes or fragments into open conflict

- Social institutions either adapt or fail

2050-2100: Living with Consequences

- After 2050, we’re largely living with decisions made earlier

- Adaptation and survival rather than prevention

- The question shifts from “can we avoid it?” to “can we survive it?”

The Survival Question: Can Humanity Persist?

Will humans go extinct if these trends continue? Probably not—humans are remarkably adaptable and geographically dispersed.

But “survival” isn’t the right standard. The questions are:

How many survive?

- Current: 8 billion

- Severe degradation scenario: 3-5 billion (through famines, conflicts, pandemics, reduced fertility)

- Catastrophic collapse scenario: 500 million – 2 billion

- The gap is filled by unfathomable suffering

Under what conditions?

- Advanced industrial civilization requires complex supply chains, energy abundance, political stability, skilled workforces

- These could be lost even with substantial population survival

- We could have billions of humans living in pre-industrial conditions with collapse having destroyed the knowledge, infrastructure, and resources needed to rebuild

With what cultural continuity?

- Many of humanity’s cultural achievements (languages, arts, knowledge traditions, philosophical systems) could be lost

- The humans who survive might have little connection to human civilization as we understand it

With what future potential?

- If we exhaust easily-accessible fossil fuels and minerals during collapse, rebuilding industrial civilization becomes nearly impossible

- We could lock humanity into a permanent pre-industrial state

- This is the “only one shot at modernity” hypothesis—if we blow it now, we may never get another chance

The Historical Precedents: What Civilizational Collapse Looks Like

We have examples, though none at global scale:

Roman Empire (Western)

- Population in collapsed regions fell by 50-75%

- Literacy nearly disappeared outside monasteries

- Technological knowledge lost (concrete, aqueducts, governance systems)

- Recovery took 800-1000 years

- Dark Ages were genuinely dark

Mayan Civilization

- Population fell by 90% in some regions

- Cities abandoned, reclaimed by jungle

- Writing system lost (only rediscovered in 20th century)

- The civilization disappeared so thoroughly we still don’t fully understand why

Bronze Age Collapse

- Multiple civilizations collapsed simultaneously (~1200 BCE)

- Writing disappeared in some areas for centuries

- International trade networks dissolved

- Took 400+ years to recover

Easter Island

- Population collapsed after deforestation

- Civil war and cannibalism

- Lost the capability to build the ships needed to escape

- Permanent isolation until European contact

The common patterns:

- Collapse is faster than recovery

- Knowledge is lost rapidly, regained slowly or never

- Population crashes are severe

- Recovery isn’t guaranteed—some civilizations never recovered

But crucially: These were regional. Collapse in one place allowed recovery through contact with others. A global collapse has no such backstop.

The Existential Risk Calculation

Some risks threaten humanity’s entire future, not just the present generation:

Nuclear War: Current arsenals could cause nuclear winter—cooling that crashes agriculture globally. Mass starvation, possibly human extinction or reduction to small populations. With deteriorating international relations and more nuclear powers, risk is rising.

Engineered Pandemic: A modified pathogen with high lethality and transmissibility could theoretically kill billions before containment. As biotechnology advances and spreads, this becomes technically easier each year.

Misaligned AI: If we create artificial superintelligence that pursues goals misaligned with human welfare, and we can’t control or stop it, the outcomes could range from permanent bad governance to human extinction.

Runaway Climate Change: If feedback loops create unstoppable warming (the “Venus scenario”), Earth becomes uninhabitable. Most scientists think this unlikely, but “unlikely” isn’t “impossible.”

Current trajectory: We’re increasing the probability of all these risks simultaneously while reducing our collective capacity to respond.

The Psychological and Philosophical Implications

Living with Doom

What does it mean to understand this trajectory and continue functioning? Humans face three psychological responses:

Denial: “It won’t be that bad / technology will save us / they’re exaggerating.” This is psychologically protective but prevents action.

Nihilism: “We’re doomed anyway, nothing matters.” This is psychologically destructive and ensures doom through inaction.

Active Hope: “Outcomes aren’t determined, and effort matters even if success isn’t guaranteed.” This is psychologically healthiest and strategically optimal.

The data suggests grounds for active hope are thin but not absent. The next 10 years genuinely do determine whether we hit severe degradation or muddling through scenarios. Individual and collective action matters at the margins—and margins determine which tipping points we cross.

The Ethical Implications

If you believe these trends are likely:

For individuals: What obligations do you have? To prepare? To fight? To enjoy life while possible? To have children (giving them life) or not (sparing them suffering)?

For societies: What is owed to future generations when present actions lock them into catastrophe? This is arguably the greatest moral crime in human history—knowingly damaging the future for present convenience.

For the species: Do we have obligations to preserve human civilization beyond our own lifespan? To Earth’s biosphere? To the potential of consciousness in the universe?

These aren’t abstract questions—they determine how we should live now.

The Case for Non-Zero Hope

I’ve painted a grim picture because the question was “if present trends continue.” But present trends don’t continue automatically—they’re the product of choices.

What could change trajectories:

- Catalyzing crises: A major but survivable crisis (regional nuclear weapon use, catastrophic pandemic, climate disaster affecting rich countries) could shock the system into cooperation—historical precedent exists (WWII → UN, Great Depression → New Deal).

- Technological breakthroughs: Fusion energy, carbon capture, synthetic food, or other innovations could change constraint math fundamentally.

- Political transformation: Mass movements have changed seemingly impossible situations before (civil rights, decolonization, fall of communism). Younger generations might force change their elders couldn’t.

- Enlightened self-interest: As consequences become undeniable, even self-interested actors might recognize that everyone loses from collapse and cooperation serves their interests.

- Cultural evolution: Human values and norms change. The “moral circle” has expanded historically (from tribe to nation to humanity). It could expand to include future generations more meaningfully.

- Institutional adaptation: Sometimes institutions surprise us by adapting rapidly when circumstances demand it.

The probability game: Even 5-10% chance of transformation is worth fighting for. The alternative is accepting worse outcomes as inevitable. Moreover, efforts that fail to prevent collapse still matter—they determine whether we hit severe degradation versus catastrophic collapse, whether 2 billion die or 6 billion die, whether recovery takes decades or centuries.

Conclusion: The Fork in the Road

We’re at a civilizational fork:

Path A (Current Trajectory): Military spending continues escalating. International cooperation deteriorates. Climate action remains insufficient. Technology develops without governance. Inequality grows. This leads with 50-70% probability to severe degradation or worse—billions suffer, civilizations collapse in regions, humanity’s potential is dramatically reduced.

Path B (Transformation): Major crisis or political movement catalyzes fundamental change. Resources reallocate from military to human development. International cooperation strengthens. Climate stabilizes at 2°C. Technology comes under governance. Inequality reduces. This seems unlikely (5-10% probability) but possible.

The timing: The next 10-20 years determine which path we follow. After 2040, we’re largely locked in.

The prognosis if things continue as they are: Severe degradation of human civilization, billions of preventable deaths, loss of cultural achievements, reduced future potential, and possible lock-in to permanent pre-industrial conditions. Not extinction, but a future so diminished from present potential as to constitute a tragedy of cosmic proportions.

The trends are negative. The momentum is substantial. The resistances are deep. But outcomes aren’t determined—they’re probabilistic. And probability responds to effort.

The question isn’t “will we be okay?”—we won’t, not if things continue. The question is: “How bad will it be, and what are we willing to do to shift those odds?”

You can also access the latest news at this address: www.whatfinger.com

-

11 Countries That Will Likely to Collapse by 2040

The most shocking videos in the world! This video actually shows us what the secret of the Trump family is related to their expressive health!!! Video HERE.

“This article was created for educational purposes”

Predicting outright state collapse is inherently uncertain, but by 2040 several countries face materially elevated risk of severe state failure or collapse of central authority—meaning loss of effective governance over significant territory, large-scale internal conflict, or fragmentation. The following list identifies countries widely judged vulnerable by analysts, with the dominant factors driving risk for each. This is a probabilistic assessment (not a deterministic forecast); risks arise from combinations of governance failure, economic stress, demography, external interference, and climate and resource shocks.

You might be living in one of America’s deathzones and not have a clue about it

What if that were you? What would YOU do?

High-risk (elevated probability of major failure or fragmentation by 2040)

- Sudan

- Key drivers: persistent civil war since 2023 between military and multiple paramilitary factions; fractured elites; collapsed economy; humanitarian catastrophe; regional proxy interventions; armed militias controlling territory. Absent a credible peace process and restoration of basic services, continued fragmentation and local warlord rule remain likely.

- Libya

- Key drivers: enduring rival governments and militias since 2011; localized war economies centered on oil; weak institutions; foreign military involvement from regional powers; fragmented security forces. Elections and stabilization have repeatedly failed; continuation of de facto partition or recurring armed confrontations is plausible.

- Somalia

- Key drivers: decades of weak central institutions; resilient Islamist insurgency (al-Shabaab); clan fragmentation; recurring drought and food crises; limited revenue base and heavy external dependence. Federal government holds territory intermittently; risk centers on further territorial losses to non-state actors and de facto regional autonomy.

- Yemen

- Key drivers: prolonged civil war (Houthi vs. internationally recognized government and southern movements), foreign intervention (Saudi/UAE, Iran-backed dynamics), collapsed public services, famine risk, and multiple competing authorities in north and south. A negotiated nationwide settlement before 2040 is possible but not assured; continued partition or frozen conflict is likely without major shifts.

Significant-concern (substantial vulnerability, where collapse is a realistic tail outcome under adverse shocks)

- Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

- Key drivers: vast territory with weak state reach, numerous armed groups in the east, fragile institutions, resource-driven local conflicts, poor infrastructure, and refugee flows. A regional conflagration or intensified localized state retreat could yield large-scale governance collapse in parts of the country.

- Haiti

- Key drivers: chronic political instability, powerful gangs controlling large urban areas (Port-au-Prince), weak security forces, economic collapse, natural disasters, and limited institutional capacity. Without decisive security reform and economic stabilization, de facto governance vacuums and quasi-failed-state dynamics will likely persist or worsen.

BREAKING NEWS: All Americans Will Lose Their Home, Income And Power By December 17, 2025

- Afghanistan

- Key drivers: the Taliban’s hold since 2021 has not produced unified, durable governance across ethnic lines; economic collapse, international isolation, insurgent pockets, factionalism, and climate-driven shocks. The risk is not classic internationalized collapse but fragmentation, governance breakdown in provinces, and potential return of competing armed groups.

- South Sudan

- Key drivers: weak institutions since independence, ethnicized politics, recurrent violence, dependence on oil revenues, poor service delivery, and climate stress on pastoralist livelihoods. Recurrent localized breakdowns remain likely; a full reversion to widespread civil war is a significant tail risk.

Medium-concern (fragility that could tip under severe economic, political, or climate shocks)

- Lebanon

- Key drivers: economic meltdown, currency collapse, sectarian/political paralysis, refugee burden, and state delegitimization. Collapse into prolonged governance paralysis and localized militias is possible if economic conditions and patronage networks deteriorate further.

- Pakistan

- Key drivers: economic crisis, political-military friction, extremist insurgency pockets, water scarcity, and institutional fragility. Full state collapse is low-probability, but severe governance crises, localized breakdowns, or loss of state capacity in border regions could occur under large shocks.

- Nigeria

- Key drivers: insurgency in the northeast (Boko Haram/IS affiliate), banditry and farmer–herder conflict in the middle belt, separatist pressures in the southeast, weak logistics and constrained fiscal space. Collapse of the whole state is unlikely, but protracted fragmentation or long-term erosion of state authority in large regions is a material risk.

Cross-cutting systemic factors that increase collapse risk

- Weak political institutions and elite fragmentation: personalized rule, lack of legitimate inter-group power-sharing, or competing centers of power increase likelihood of violence and devolution of authority.

- Economic collapse and fiscal insolvency: hyperinflation, loss of export revenue (commodity shocks), unsustainable debt, and inability to pay security forces degrade state capacity rapidly.

- Prolonged armed conflict and proliferation of non-state armed actors: when militias, insurgents, or criminal gangs control territory and revenue streams, central authority becomes nominal.

- External interference and proxy wars: foreign militaries, weapons flows, and proxy backers extend and complicate domestic conflicts, preventing settlement.

- Climate change and resource stress: droughts, floods, crop failures, and water scarcity exacerbate displacement, food insecurity, and competition over land.

- Demographic pressures and youth unemployment: large cohorts of unemployed young people create recruitment pools for armed groups and increase social volatility.

- Humanitarian crises and displacement: mass refugee movements and internal displacement overload state and regional systems, eroding legitimacy and control.

How to interpret this assessment

- Collapse is not binary; states often move into zones of partial failure where central control coexists with autonomous regions, militia rule, or competing authorities. The list above highlights countries where such severe deterioration is plausible by 2040 if current trajectories persist or if adverse shocks occur.

- Time horizons and probabilities matter: some countries face near-term high risk (next few years), others face chronic fragility that could tip under repeated or large shocks before 2040.

- External and internal policy choices matter: international mediation, targeted economic support, inclusive political settlements, and climate adaptation can materially change trajectories.

Indicators to watch through 2040 (early warning)

- Sharp collapse in government revenue and public-sector payrolls (security forces unpaid).

- Loss of monopoly on violence in large population centers or resource-producing regions.

- Rapid increases in internally displaced people and refugee flows across borders.

- Significant foreign military bases, covert arms flows, or open proxy deployments.

- Breakdown in basic services (electricity, health, food distribution) for sustained periods.

Sources and limits

- This assessment synthesizes patterns observed in conflict studies, fragile-states indices, UN humanitarian reporting, and regional expert analyses through May 2024. New diplomatic settlements, reform breakthroughs, or large-scale international interventions could alter trajectories before 2040.

Warning!!! First Signs That U.S. Consumers Are In Very Serious Trouble

If you have any dissatisfaction with my content, you can tell me here and I will fix the problem, because I care about every reader and even more so about your opinion!

You can also access the latest news at this address: www.whatfinger.com

- Sudan

-

Interesting! A Timeline of the End Game for Human Civilization

Humanity has constructed a doomsday Deadman switch that threatens civilization. Climate destruction will make it increasingly difficult to avoid the looming global nuclear catastrophe we’ve created.

Here’s how our future might unravel:

Late 2020s: Climate Red Alert and Infrastructure Strain

By the late 2020s, Earth’s climate is in unprecedented turmoil. Global average temperatures are consistently 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. Each year brings record-breaking heatwaves, “freak” floods, and droughts that batter infrastructure. Coastal cities flood more frequently, roads buckle in extreme heat, and power grids strain under surging demand for cooling.

This cascade of climate disasters sets the stage for a systemic collapse: as societies grapple with runaway warming, the resilience of critical infrastructure (power, water, transit) erodes.

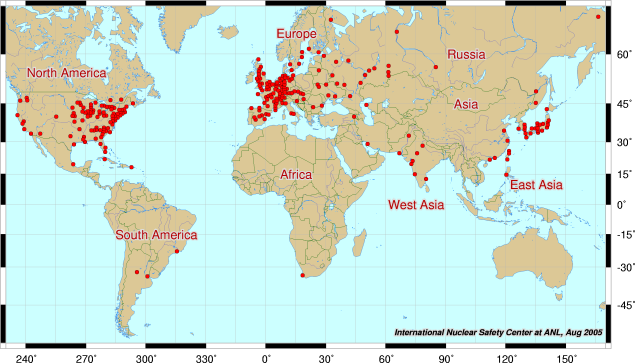

Energy systems enter a crisis even before 2030. Nuclear power, which in 2025 still provided about 9% of the world’s electricity from ~440 reactors, becomes increasingly unreliable. Many nuclear plants struggle with climate stresses: cooling water sources heat up in summer, forcing reactors to reduce output or shut down to avoid unsafe temperatures. For example, a 2028 European heatwave pushes river and sea temperatures above 25 °C, triggering emergency shutdowns at multiple reactors that cannot be cooled effectively.

At the same time, stronger storms and floods threaten reactor safety. Dozens of reactors worldwide are unprepared for extreme flooding, meaning a dam failure or storm surge could lead to a Fukushima-scale accident. Worrisome reports emerge of power plants in floodplains and coasts where defenses are overtopped by rising seas and torrential rains.

By 2029, global carbon output remains high, and natural feedback loops are kicking in. In the Arctic, permafrost thaws and releases methane creating a vicious warming cycle where initial warming triggers more emissions, leading to even more warming. Scientists caution that a tipping point is near, beyond which climate change becomes self-perpetuating (a true “runaway” scenario).

Society approaches 2030 in a precarious state: aware of looming catastrophe yet unprepared for its speed. The stage is set for the coming collapse, with power grids and nuclear facilities – the backbone of the industrial world – already under severe strain.

Early 2030s: Blackouts and the First Reactor Crises

2030 marks the breaking point.

A confluence of climate catastrophes collapses power grids across multiple continents. A severe global heatwave in the summer of 2030 brings record electricity demand while many power plants (nuclear and coal alike) are derated or offline due to overheating coolant water.

Then powerful Category 5 storms strike in succession: one hurricane inundates the U.S. Eastern seaboard, while an unprecedented typhoon swamps Southeast Asia. These disasters knock out transmission lines and flood key substations, leading to prolonged blackouts in dozens of major cities. Emergency systems are overwhelmed. With communications down and transportation paralyzed, manpower shortages become acute – many operators and engineers cannot reach their stations.

Nuclear power plants are among the first to feel the emergency. Grid failure triggers automatic reactor SCRAMs (rapid shutdowns) at plants from Florida to France. Control rods halt the fission reactions, but decay heat in reactor cores still needs cooling for days to prevent meltdown.

Normally, backup diesel generators would power the cooling pumps, but the scale of the blackout means diesel resupply is uncertain and some generators fail in flooded facilities. In a grim reflection of 2011’s Fukushima disaster, several coastal reactors lose all power as storm surges drown their backup generators.

Within hours to days, the first meltdowns occur.

In 2031, a reactor in South Asia becomes a flashpoint: its cooling pumps falter after the grid collapse, leading the core to overheat. The reactor’s heart melts through containment in a matter of days, releasing a plume of radioactive steam and debris.

Nearby, an even greater danger unfolds: the plant’s spent fuel pool, packed with years of highly radioactive spent rods, boils dry without cooling. Exposed to air, the zirconium cladding of the fuel ignites, triggering a fire that belches long-lived radioisotopes directly into the atmosphere. This nightmare scenario – once narrowly avoided at Fukushima by heroic ad-hoc measures – now plays out in full.

Local and regional consequences are immediate and harrowing. Authorities, already struggling with disaster response, hastily order mass evacuations around stricken plants. In the South Asia incident, a radius of 30 km is declared a no-go zone as radiation levels spike. Over one million people are displaced in this region alone, fleeing what swiftly becomes a nuclear dead zone. Many receive significant radiation doses during the chaotic evacuation, trapped by traffic jams under drifting fallout.

Comparisons are made to Chernobyl’s 1986 evacuation – there, 130,000 people were permanently resettled and a 1,000-square-mile exclusion zone established – but the 2031 event affects an even larger population in a densely settled area.

Photo by Dasha Urvachova / Unsplash Nearby countries track the radioactive cloud as it crosses borders. Within days, radioactive iodine and cesium are detected in cities hundreds of kilometers downwind. Governments distribute iodine tablets to help block uptake of radioactive iodine in thyroid glands, recalling measures taken after Chernobyl and Fukushima. Farmers in downwind regions watch in despair as cesium-137 contaminates soil and crops, knowing from past accidents that those lands may be unsafe for farming for decades. (After Chernobyl, for instance, radio-cesium lingering in soils kept pastures in parts of Europe under restriction for over 20 years.)

Globally, these first reactor crises send a chilling signal. Airborne radiation from the fires and vented steam reaches the upper atmosphere and begins circling the planet. Within weeks, trace amounts of cesium-137 and strontium-90 are found in faraway monitoring stations.

While the initial fallout poses the greatest danger locally, the global dispersion of radionuclides raises alarms. Public health experts warn that even low-dose fallout on crops could, when multiplied across the world, elevate cancer risks and contaminate food supplies. International markets are rocked as nations ban produce and grain imports from entire regions. The economic shock compounds the physical destruction: already destabilized by climate disasters, the global supply chain further fractures under fear of radiation in goods.

Perhaps most critical for what comes next, these early accidents erode the capacity to respond to future crises. Emergency workers who heroically battled the first meltdowns (hosing overheating reactors, attempting improvised cooling) have suffered radiation exposure or exhaustion. Large swaths of power grid remain offline, making rolling blackouts the new normal even in areas not directly hit by climate events. This energy shortage slows recovery efforts and undermines the cooling and monitoring systems at other nuclear sites. By 2032, the world faces a stark reality: roughly 10% of nuclear reactors worldwide are in some stage of crisis – either already melted down, or scrammed and struggling to keep their hot cores and spent fuel safe. What was once unthinkable now seems inevitable.

Mid-2030s: Cascading Meltdowns Across the World

As 2035 approaches, the situation spirals into a cascade of nuclear calamities. Ongoing climate chaos keeps hammering human systems. Year after year, megastorms, wildfires, and heatwaves pummel regions before they can recover. The compounded infrastructure damage means many areas have only intermittent electricity and scarce supplies.

In this environment, about half of the world’s nuclear reactors are effectively left unattended or unserviceable – some due to direct disaster impacts, others because manpower and resources have collapsed in the region. Governments in relatively stable areas attempt to initiate orderly shutdowns of reactors as a preventative measure, but even a shut reactor needs years of active cooling and oversight. In many cases, those best efforts falter.

By 2033–2035, a wave of reactor meltdowns unfolds on nearly every continent.

Nuclear reactors around the world The numbers are staggering. What started with a few isolated accidents in 2030–32 explodes into dozens of sites in crisis. Older nuclear stations prove especially vulnerable: lacking passive cooling features, they succumb quickly when grid power and backups fail. Newer reactors touted as “meltdown-proof” also face unforeseen challenges – coolant reservoir tanks run dry when maintenance crews vanish, or hydrogen explosions (like those that blew apart Fukushima’s reactor buildings) occur due to unvented pressure.

Spent fuel pool fires add to the nightmare at many sites; analysts later estimate that these pool fires released even more radiation than the reactor core meltdowns in several cases, since pools often contained decades of fuel assemblies (holding up to 10× the long-lived radioactivity of a reactor core in each pool).

Each collapsing plant creates its own radiation footprint. By the mid-2030s, a patchwork of radioactive exclusion zones scars the Northern Hemisphere. In Eurasia, multiple zones – from Western Europe through Russia, South Asia, and East Asia – dot the map where reactors have failed. Some of these zones begin to overlap, forming a virtually continuous swath of contaminated land in parts of Europe and Asia.

In Western Europe, for example, meltdowns at two French reactors and one German reactor in 2034 force evacuations that cover large parts of the Rhine valley. Later, a catastrophe at Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia plant (already endangered for years prior) adds to the chain, rendering areas along the Dnieper River highly radioactive once again.

North America is not spared: a meltdown at an aging Midwest U.S. plant sends radiation across several states, and Canada’s Ontario reactors – shut down due to power loss – suffer a fuel pool fire that spreads contamination through the Great Lakes region.

In total, roughly 50% of the world’s 400+ reactors are now either destroyed or abandoned. Humanity suddenly finds itself living with hundreds of Chernobyl-sized disasters at once.

Local and regional consequences reach an apocalyptic scale. Hundreds of millions of people become actual or potential refugees from high-radiation areas. Major cities near failed plants are emptied: by 2035, regions like the French Riviera, the North China Plain, and the U.S. eastern seaboard have pockets that resemble Pripyat – ghost cities left to wild animals.

The contamination of land and water is immense. Isotopes like cesium-137 and strontium-90 settle into agricultural soils. Just as Chernobyl’s fallout once contaminated 200,000+ square kilometers of Europe to some degree, the 2030s meltdowns contaminate vast expanses of the globe. Agricultural experts estimate that a significant fraction of the world’s breadbaskets are now tainted by radioactive fallout.

For example, the Punjab region and the American Midwest both see cesium levels in soil far above safe farming limits, threatening global grain supplies. In many countries, the choice is stark: eat potentially contaminated food or starve.

Livestock that graze on fallout-blanketed pastures accumulate radionuclides in their meat and milk, as British sheep did for decades after Chernobyl. Governments impose strict bans on food exports from these zones, and global food prices skyrocket. Famine looms for countries that relied on imports from now-irradiated farmlands.

Photo by Ian Cylkowski / Unsplash Beyond human habitations, ecosystems suffer radiological damage layered on top of climate stress. Forests downwind of reactor accidents turn brown and silent as foliage and wildlife absorb heavy doses of radiation. In some intensely contaminated zones, an eerie calm prevails – reminiscent of how the core area around Chernobyl became an accidental wildlife refuge, but one where many organisms die young or show mutations.

Initially, high radiation kills or stunts many plants and animals. Forests die and animal populations plummet. Over the later 2030s, some wildlife returns to abandoned zones, benefiting from the lack of humans. However, in areas of very high contamination, biodiversity remains lower and animals show signs of chronic radiation exposure.

The web of life is poisoned: radioactive cesium and strontium work their way up food chains, affecting predators and prey alike. Combined with the ongoing climate upheavals (heat stress, wildfires, habitat shifts), the added burden of radiation pushes many species to extinction in contaminated regions. Aquatic ecosystems are also hit – radioactive runoff flows into rivers and seas, causing fish kills and long-term mutations in fish reproductive cycles.

The global consequences of this mid-2030s nuclear cascade are profound. Atmospheric circulation transports radioactive pollution around the world. By 2035–2036, background radiation levels have risen noticeably above 2020s norms in both hemispheres. Radioactive particles from multiple meltdowns are detected in the Arctic and even the Antarctic, having been carried by air currents. Although concentrations far from accident sites are low, no corner of the planet is truly untouched.

In the Northern Hemisphere, intermittent waves of fallout descend whenever rain clouds scavenge particles from the upper atmosphere – a phenomenon similar to the fallout patterns observed after nuclear weapons tests and Chernobyl, but now sustained by ongoing reactor fires and spent-fuel blazes. Public health experts warn that long-term cancer rates will climb worldwide; every additional becquerel in our food and water increases risks.

By the late 2030s, the world’s socio-economic order has largely disintegrated. The combination of climate catastrophe and radioactive contamination fractures the globalized economy. International travel is nearly nonexistent both because of infrastructure breakdown and fear of radiation exposure on long journeys. Trade in food and goods has devolved into ad-hoc local barter, since centralized distribution is impossible under constant disaster.

Regions that remain habitable form “safe zones” – relatively less contaminated and with tolerable climate – mostly in the far southern hemisphere and a few remote northern areas. For instance, parts of New Zealand, Patagonia, and Siberia (far from any meltdown sites and somewhat buffered by distance) become refuges for those able to relocate. Even so, these areas face their own challenges from extreme weather and inflows of refugees.

Humanity’s population shrinks precipitously due to famine, conflict, and radiation-related illness. What was roughly 8 billion people in 2020 falls by at least hundreds of millions (edit: more likely billions) by 2040. Those losses stem not only from immediate disaster casualties but also from secondary effects: hunger, lack of medical care, and weakened immune systems in a ravaged environment.

2040s: The Toxic Legacy Settles In

By the 2040s, the frantic pace of new catastrophes slows somewhat – not because the crises are solved, but because so much has already collapsed. Most of the vulnerable nuclear reactors have already broken down by this point or were pre-emptively shut. The ones that survived the 2030s are primarily in regions that remained functional enough to manage a safe cold shutdown or have newer designs with passive cooling. However, the world now faces the long aftermath of what has happened. The 2040s are a bleak decade of enduring fallout (literal and figurative), where humanity grapples with the toxic legacy of hundreds of reactor failures amid a climate that remains hostile.

One grim reality sets in: the radioactive contamination is far from a short-term problem. Many of the isotopes released have half-lives measured in decades or longer, meaning the radiation will persist for generations. For example, cesium-137 (half-life ~30 years) and strontium-90 (half-life ~29 years) remain abundant in the soils of meltdown zones and downwind regions.

These isotopes mimic vital nutrients (cesium behaves like potassium, strontium like calcium), so they continuously cycle through plants, animals, and water. Crops grown in contaminated soil uptake cesium; grazing animals concentrate it in their flesh; humans who consume those foods further concentrate it in their bodies. In the 2040s, scientists document how radioactivity has infiltrated the global food chain. Traces of cesium-137 show up in grain and milk even in “safe” zones, due to minute fallout that has spread worldwide.